In this post I’ll describe how to simulate or sample a homogeneous Poisson point process on the surface of a sphere. I have already simulated this point process on a rectangle, triangle disk, and circle.

Of course, by sphere, I mean the everyday object that is the surface of a three-dimensional ball, where this two-dimensional object is often denoted by \(S^2\). Mathematically, this is a generalization from a Poisson point process on a circle, which is slightly simpler than randomly positioning points on a disk. I recommend reading those two posts first, as a lot of the material presented here builds off them.

I have not needed such a simulation in my own work, but I imagine there are many reasons why you would want to simulate a Poisson point process on a sphere. As some motivation, we can imagine these points on a sphere representing, say, meteorites or lightning hitting the Earth.

The generating the number of points is not difficult. The trick is positioning the points on the sphere in a uniform way. As is often the case, there are various ways to do this, and I recommend this post, which lists the main ones. I will use two methods that I consider the most natural and intuitive ones, namely using spherical coordinates and normal random variables, which is what I did in the post on the circle.

Incidentally, a simple modification allows you to scatter the points uniformly inside the sphere, but you would typically say ball in mathematics, giving a Poisson point process inside a ball; see below for details.

Steps

As always, simulating a Poisson point process requires two steps.

Number of points

The number of points of a Poisson point process on the surface of a sphere of radius \(r>0\) is a Poisson random variable with mean \(\lambda S_2\), where \(S_2=4\pi r^2\) is the surface area of the sphere. (In this post I give some details for simulating or sampling Poisson random variables or, more accurately, variates.)

Locations of points

For any homogeneous Poisson point process, we need to position the points uniformly on the underlying space, which is in this case is the sphere. I now outline two different methods for doing this.

Method 1: Spherical coordinates

The first method is based on spherical coordinates \((\rho, \theta,\phi)\), where the radial coordinate \(\rho\geq 0\), and the angular coordinates \(0 \leq \theta\leq 2\pi\) and \(0\leq \phi \leq \pi\). The change of coordinates gives \(x=\rho\sin(\theta)\cos(\phi)\), \(y=\rho\sin(\theta)\sin(\phi)\), and \(z=\rho\cos(\phi)\).

Now we use Proposition 1.1 in this paper by Pitman and Ross. For each point, we generate two uniform variables \(V\) and \(\Theta\) on the respective intervals \((-1,1)\) and \((0,2\pi)\). Then we place the point with the Cartesian coordinates

$$X = r \sqrt{1-V^2} \cos\Theta, $$

$$Y = r \sqrt{1-V^2}\sin\Theta, $$

$$ Z=r V. $$

This method places a uniform point on a sphere with a radius \(r\).

How does it work?

I’ll skip the precise details, but give some interpretation of this method. The random variable \(\Phi := \arccos V\) is the \(\phi\)-coordinate of the uniform point, which implies \(\sin \Phi=\sqrt{1-V^2}\), due to basic trigonometric identities. The area element in polar coordinates is \(dA = \rho^2 \sin\phi d\phi d\theta \), which is constant with respect to \(\theta\). After integrating with respect to \(\phi\), we see that the random variable \(V=\cos\Phi\) needs to be uniform (instead of \(\Phi\)) to ensure the point is uniformly located on the surface.

Method 2: Normal random variables

For each point, we generate three standard normal or Gaussian random variables, say, \(W_x\), \(W_y\), and \(W_z\), which are independent of each other. (The term standard here means the normal random variables have mean \(\mu =0\) and standard deviation \(\sigma=1\).) The three random variables are the Cartesian components of the random point. We rescale the components by the Euclidean norm, then multiply by the radius \(r\), giving

$$X=\frac{rW_x}{(W_x^2+W_y^2+W_z^2)^{1/2}},$$

$$Y=\frac{rW_y}{(W_x^2+W_y^2+W_z^2)^{1/2}},$$

$$Z=\frac{rW_z}{(W_x^2+W_y^2+W_z^2)^{1/2}}.$$

These are the Cartesian coordinates of a point uniformly scattered on a sphere with radius \(r\) and a centre at the origin.

How does it work?

The procedure is somewhat like the Box-Muller transform in reverse. In the post on the circle setting, I gave an outline of the proof, which I recommend reading. The joint density of the normal random variables is from a multivariate normal distribution with zero correlation. This joint density is constant on the sphere, implying that the angle of the point \((W_x, W_y, W_z)\) will be uniformly distributed.

The vector formed from the normal variables \((W_x, W_y,W_z)\) is a random variable with a chi distribution. We can see that the vector from the origin to the point \((X,Y,Z)\) has length one, because we rescaled it with the Euclidean norm.

Plotting

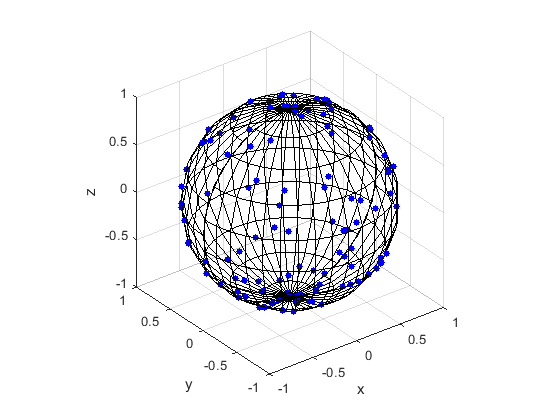

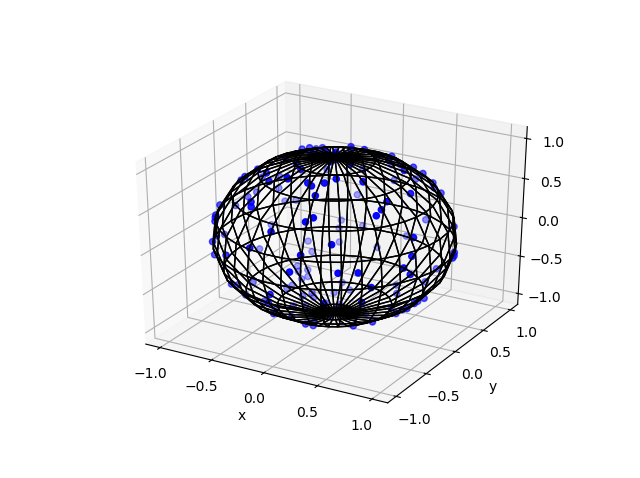

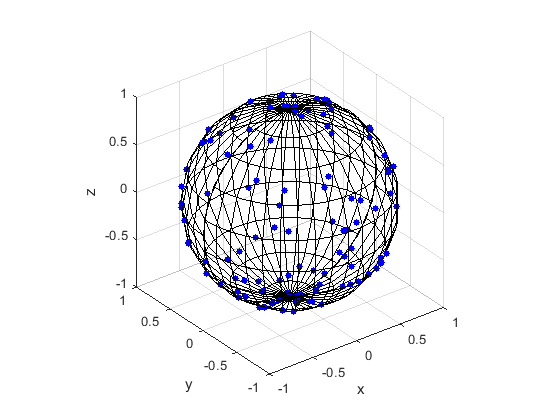

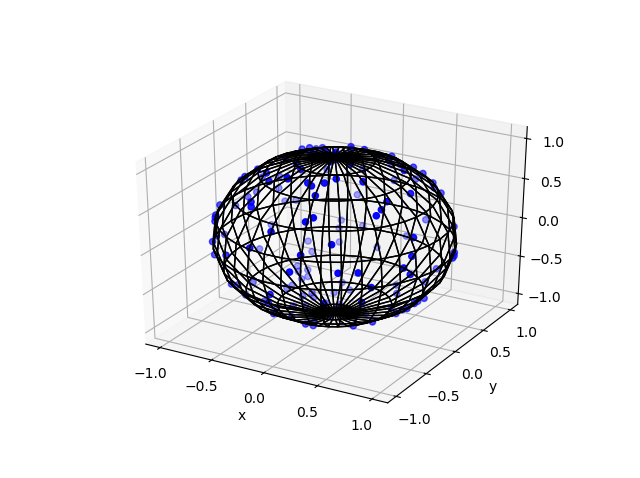

Depending on your plotting software, the points may more resemble points on an ellipsoid than a sphere due to the different scaling of the x, y and z axes. To fix this in MATLAB, run the command: axis square. In Python, it’s not straightforward to do this, as it seems to lack an automatic function, so I have skipped it.

Results

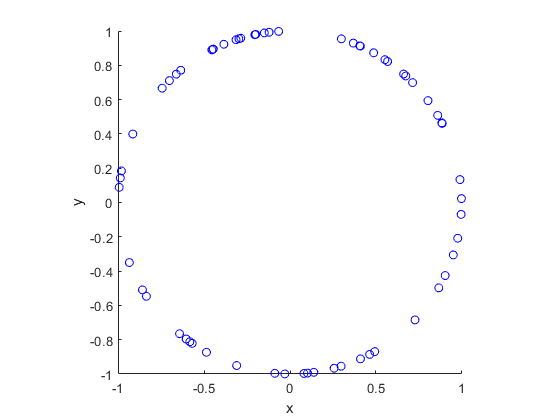

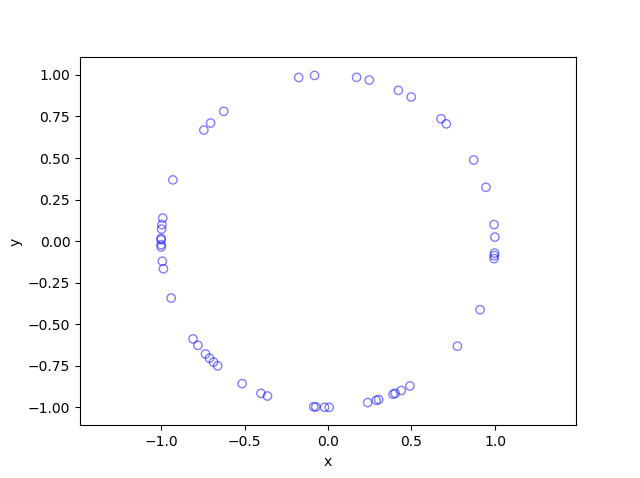

Here are some results produced by code written in MATLAB and Python. The blue points are the Poisson points on the sphere. I have used a surface plot (with clear faces) to illustrate the underling sphere in black.

MATLAB

Python

Note: The aspect ratio in 3-D Python plots tends to squash the sphere slightly, but it is a sphere.

Code

The code for all my posts is located online here. For this post, the code in MATLAB and Python is here. In Python I used the library mpl_toolkits for doing 3-D plots.

Poisson point process inside the sphere

Perhaps you want to simulate a Poisson point process inside the ball. There are different ways we can do this, but I will describe just one way, which builds off Method 1 for positioning the points uniformly. (In a later post, I will modify Method 2, giving a way to uniformly position points inside the ball.)

For this simulation method, you need to make two simple modifications to the simulation procedure.

Number of points

The number of points of a Poisson point process inside a sphere of radius \(r>0\) is a Poisson random variable with mean \(\lambda V_3\), where \(V_3=4\pi r^3\) is the volume of the sphere.

Locations of points

We will modify Method 1 as outlined above. To sample the points uniformly in the sphere, you need to generate uniform variables on the unit interval \((0,1)\), take their cubic roots, and then, multiply them by the radius \(r\). (This is akin to the step of taking the square root in the disk setting.) The random variables for the angular coordinates are generated as before.

Further reading

I recommend this blog post, which discusses different methods for randomly placing points on spheres and inside spheres (or, rather, balls) in a uniform manner. (Embedded in two dimensions, a sphere is a circle and a ball is a disk.)

Our Method 2 for positioning points uniformly, which uses normal variables, comes from the paper:

- 1959, Muller, A note on a method for generating points uniformly on n-dimensional spheres.

This sampling method relies upon old observations that normal variables are connected to spheres and circles. I also found this post on a similar topic. Perhaps not surprisingly, the above paper is written by the same Muller behind the Box-Muller method for sampling normal random variables.

Update: The connection between the normal distribution and rotational symmetry has been the subject of some recent 3Blue1Brown videos on YouTube.

Here is some sample Python code for creating a 3-D scatter plot.